Free-Energy Perturbation

Free-energy perturbation (FEP) is a physics-based method for predicting protein–ligand binding affinity. Strictly speaking, FEP is a way to use statistical mechanics to estimate the difference in free energy between two states, and the mathematics of FEP can be used to approach any number of problems: ligand solvation, enzyme active sites, or the absolute protein–ligand binding affinity. (This high-level discussion doesn't do justice to the elegant statistical physics that undergird FEP; for details, see this review by Darren York and this living review from Huafeng Xu and co-workers.)

In practice, most industrial FEP is "relative binding free energy" (RBFE) FEP, which uses molecular dynamics simulations in explicit solvent to evaluate relative binding free energies between closely related analogs. This enables quantitative ranking of design ideas within a congeneric series. RBFE workflows are particularly well suited to lead optimization, where chemists are repeatedly choosing among many plausible substitutions and want a predictive, assay-calibrated way to prioritize what to make next.

RBFE calculations are often used to accelerated hit-to-lead optimization in drug discovery: since running RBFE calculations is much faster than synthesizing new compounds and experimentally measuring their binding affinity calculations, free-energy calculations can be used to triage molecules before synthesis to accelerate timelines and improve compound prioritization.

What Running RBFE Calculations Requires

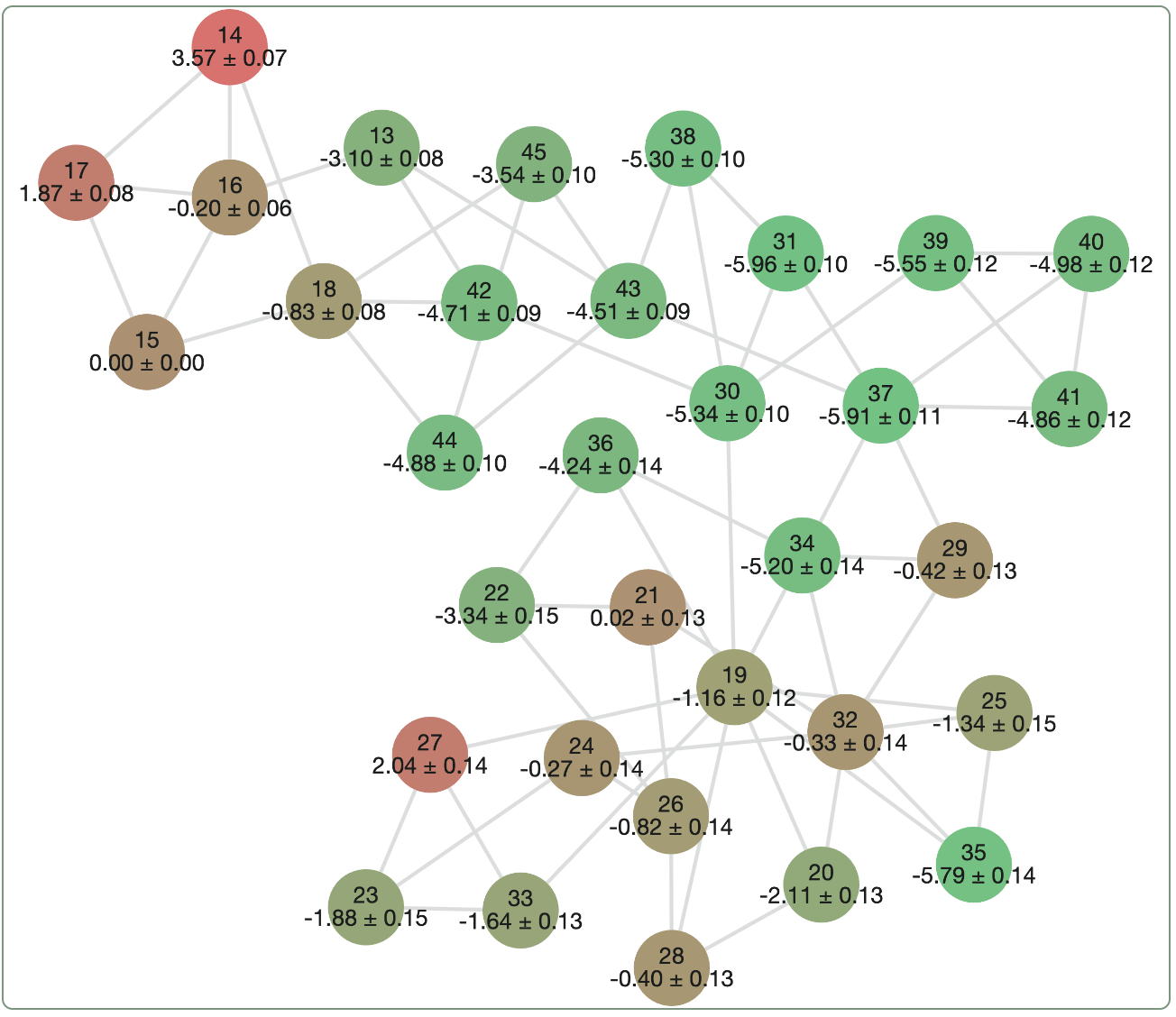

Here's what an example of an RBFE output might look like. Each graph node represents a separate ligand, and each graph edge represents a single "alchemical" FEP run that computes the difference in binding free energy between the two ligands. The results of all the edges can be combined to determine a relative ranking for all the ligands; here, the ligands shown in green are predicted to be stronger binders and the ligands shown in red and predicted to be weaker binders.

A sample relative binding free energy graph.

While other computational methods can also predict how small chemical modifications will affect binding affinity, like docking and certain co-folding methods, FEP consistently ranks among the most accurate and practically useful methods for binding-affinity prediction along a congeneric series. Unlike ML-based methods, FEP doesn't require training data, making it less susceptible to activity cliffs for ligands with structural features poorly represented in the training data. A 2023 paper from Gregory Ross and co-workers argues that FEP can even achieve performance comparable to experimental binding affinity assays.

Practical Considerations

Input Structure

The accuracy of RBFE calculations is dependent on the quality of the input poses. Typically RBFE calculations start from a crystallographically determined protein–ligand complex structure, but in silico structures generated by docking or co-folding can also be used. When using computationally determined input structures, care must be taken to ensure that the structures are physically valid and don't have interatomic clashes; Stephan Thaler and co-workers found that Boltz-2 was significantly better than Boltz-1 at generating clash-free structures suitable for FEP.

Once a single protein–ligand pose has been obtained, generating poses for analogues of the ligand is significantly simpler. Since high geometric overlap improves the convergence and performance of RBFE calculations, algorithms like maximum-common-substructure docking have been shown to outperform unconstrained docking for generating analogue poses.

Since different analogues may exist in different protonation states or as different tautomers, it's important to use chemical modeling tools to make sure the state being simulated in an RBFE calculation actually corresponds to what will exist in solution. Modeling the wrong protonation state may result in completely incorrect predictions!

Graph Construction

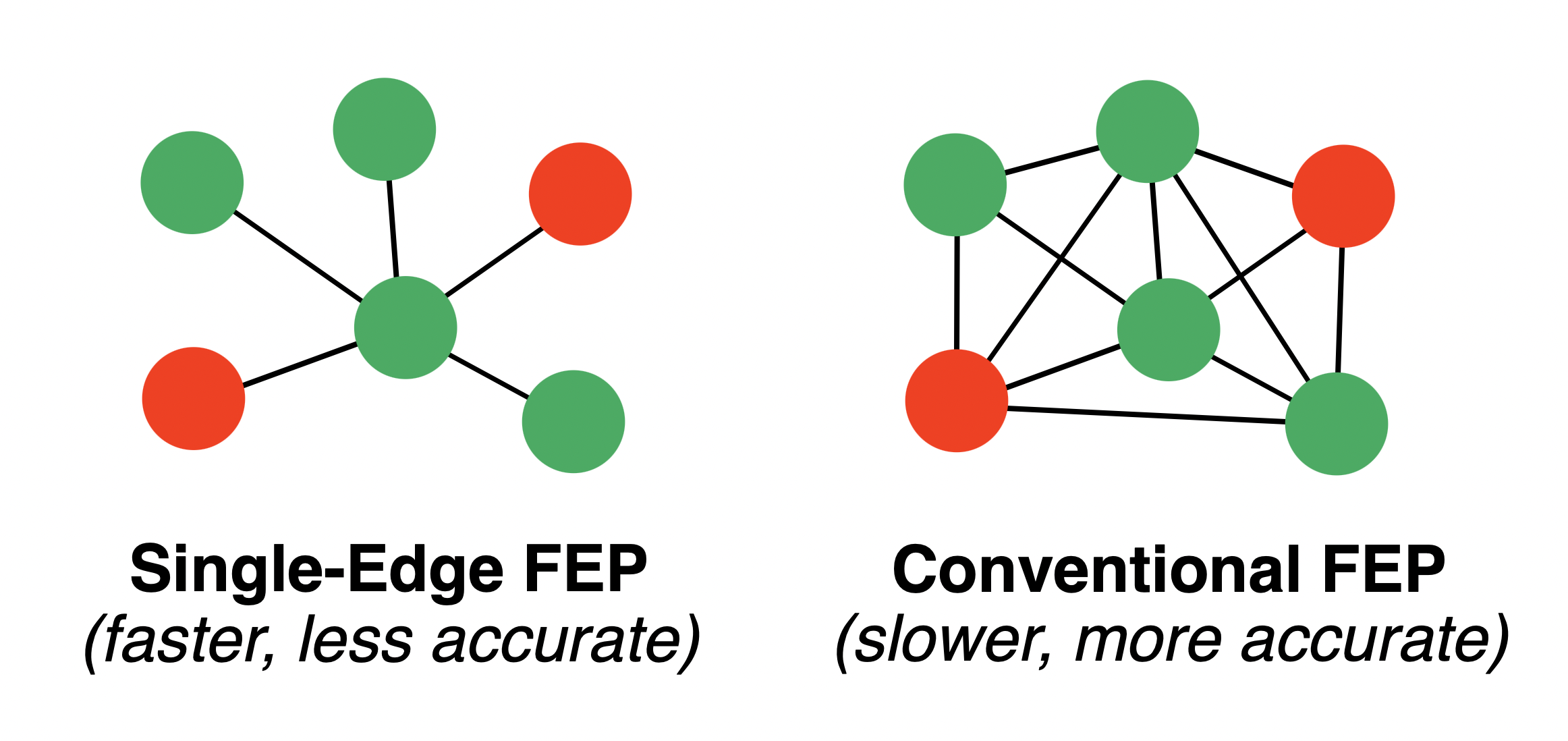

RBFE calculations build up an overall affinity ranking through many individual ligand–ligand alchemical transformations, or "legs." For a large number of ligands, figuring out which ligands to mutate into which other ligands becomes a challenging and NP-complete problem. Typical graph-construction algorithms typically return around N edges for N ligands; recent theoretical results from Mobley and co-workers suggest that at least N ln(N) edges should be used.

If maximum speed is desired, single-edge FEP schemes can be used, which sacrifice statistical accuracy but typically run about twice as fast (N edges for N ligands).

Different graph-construction strategies.

Runtime

Relative binding free-energy calculations, while faster than absolute binding free-energy calculations, are still pretty slow compared to other computational chemistry methods. As of 2025, Cresset estimates that RBFE calculations take about 10 hours per ligand, which comports with estimates from Moore and colleagues at AstraZeneca. This leads to substantial real-world costs; at current GPU rates, each computed binding affinity might cost $10 or more in underlying cloud-compute costs.

Since FEP is very computationally intensive, having access to the right GPU hardware is critical to obtain the best speed–cost profile. Some FEP implementations require scientists to bring their own infrastructure and compute hardware, while other implementations automatically allocate GPU resources in the cloud for each job.

Parameter Tuning

Many FEP implementations allow the end user to tune many degrees of freedom, like choice of poses, simulation length, number of lambda windows, graph-construction method, solvent sampling method, and more. Determining the right combination of settings to get the best results for a given system is often a non-trivial undertaking, leading to the rise of automated "protocol builders" (e.g.) to help users determine the best way to run FEP and get useful insights. (Various other automated or semi-automated schemes can be employed to solve individual parameter-selection problems: see inter alia Scott Midgley and co-workers' approach for adaptive lambda scheduling.)

Torsional Sampling

Slow torsional rotations can lead to sampling issues in free-energy perturbation because not all torsional equilibria may be adequately sampled. Ideally, the timescale of torsional interconversion would be significantly faster than the timescale of the simulation such that a significant number of torsional interconversions could be observed over the course of the simulation; recent work from Meghan Osato, Travis Dabbous, and David Mobley recommends at least 10 transitions be observed and puts forward an automated workflow to diagnose torsional-sampling issues.

Complex Conformations (e.g. Macrocycles)

FEP calculations can sometimes struggle to sample all the requisite degrees of ligand conformation motion, even when longer simulation times are used each window. Wallraven, Holmelin, and co-workers investigated the use of RBFE calculations to predict the binding affinity of macrocyclic peptides to the human adaptor protein 14-3-3; they found that standard RBFE calculations were insufficient even with 20 ns per leg, and had to use positional restraints to obtain well-converged binding-affinity predictions. Later work by Stuart Lang and co-workers studied macrocyclic analogues of pacritinib as JAK2 inhibitors and found that forcefield modifications were required to obtain optimal results from FEP.

Real-World Validation

The practical impact of FEP is best understood as an improvement in decision quality per synthesis cycle. In a fully prospective study on cathepsin L inhibitors, 36 novel compounds were synthesized and tested, and FEP-guided selections improved affinity for 8 of 10 picks, compared with 1 of 10 for other prioritization approaches evaluated alongside it. In other words, when synthesis and biology are the rate-limiting steps, increasing the hit rate of synthesized compounds directly reduces the number of design–make–test–analyze iterations required to reach a desired level of potency. This allows pre-clinical teams to work faster and spend more of their discovery budget optimizing crucial in vivo properties like permeability, bioavailability, and toxicity.

At the program level, FEP is often deployed as a pre-synthesis filter: use computation to evaluate far more ideas than can be experimentally made, then synthesize only the best supported candidates. In a large, prospective industrial deployment at Merck KGaA (2016–2019), FEP was applied across 12 targets and 23 chemical series, generating predictions for over 6,000 chemical entities and leading to more than 400 blindly predicted, novel molecules being synthesized and tested. The same report describes screening at least 50–100 ideas for custom-built libraries and aiming to screen 5–10 times more ideas than the maximum number of compounds that can be selected for synthesis. This "compute wide, synthesize narrow" strategy expands the evaluated design space without expanding wet-lab throughput and lets teams concentrate experimental effort on compounds with the highest predicted probability of delivering the next SAR advance.

Running FEP Through Rowan

Rowan is developing a modern low-cost FEP workflow designed to enable rapid and high-accuracy binding-affinity predictions at scale. We anticipate releasing this workflow via private beta in early 2026; if you're interested in being a part of this, please reach out!